THE BACKGROUND

Work on personality can be traced back to Hippocrates, the Greek physician, who spoke of four personality types: Choleric, Melancholic, Sanguine and Phlegmatic.

Sigmund Freud was the first psychologist to investigate personality specifically. Freud’s research is much criticised, most notably for the fact that it was largely based on case study evidence using a non-representative sample.

Since Freud, much of the subsequent personality research has focused on the identification of ‘traits’. Traits are mechanisms within individuals that shape the way they react in different situations. Traits are often said to summarise past behaviour and predict future. In scientific, experimental terms, research has attempted to identify the basic personality traits that reliably describe and account for the individual differences in personality between people.

Throughout the 20th Century there was a great deal of disagreement as to the specific number of traits, or factors, that exist and the literature reveals a raft of different researchers that claim to have found the answer to this question. At one end of the spectrum, Cattell identified 16 factors of personality whilst Eysenck (1967) initially claimed there were just two.

Disagreement about the number of separate factors of personality prevailed until mid-way through the second half of the 20th Century. More recent studies by McCrae and Costa (1987) have identified five core factors (sometimes known as ‘The Big Five’) as being the largest number of separate, uncorrelated dimensions of personality and many research institutions and industry professionals around the world now see a five factor representation of personality as the most valid model:

- Extraversion – assertive, active, excited, gregarious, energetic, outgoing

- Agreeableness – trusting, modest, compliant, generous, kind, sympathetic

- Attainment (often referred to as Conscientiousness) – ordered, planned, thorough, achievement-striving

- Emotionality (this includes the concept of Neuroticism) – anxious, self-conscious, impulsive, tense, worrying

- Cognition (often referred to as Openness to Experience) – ideas, curious, imaginative, insightful

MEASURING A PERSON’S PSYCHOLOGY

But how can you measure something which is inside a person’s head and, therefore, unobservable?

Psychometric assessments are standard and scientific methods used in many walks of life for measuring unobservable psychological phenomena. An obvious example in education would be ability testing children for verbal and numerical reasoning.

Psychometrics are also used extensively for personality assessment by means of an introspective (that is, subjective) self-report questionnaire. And they range from seemingly fun but worthless online quizzes on one end to serious, scientifically validated tools at the other.

The serious, scientifically validated tools have been used for decades in business, sport and the military in connection with recruitment and personal development – well known examples include Myers-Briggs, 16PF, Hogan, OPQ and the California Personality Inventory.

The underlying psychometric assessment tools embodied within Q are within the category of those serious, scientifically validated tools.

WHY DR STEVE GLOWINKOWSKI DEVELOPED THE GPI

Dr Glowinkowski as a psychologist for over 40 years found that the existing ways of assessing the five core dimensions of personality did not meet all of his needs in his consultancy work:

1. Terminology and language

Predispositions and behaviour are separate things. If a predisposition does play itself out in behaviour, it is possible that some predispositional profiles may be less positive than others.

However, there is no right and wrong in predispositions. Not only did Dr Glowinkowski find that in several of the available measures the distinction between predisposition and behaviour was not clear, but the measures also described some predispositions as more favourable than others. If predispositions are considered as bipolar, it is not then right to attribute favorability to either side or hold one pole above the other. Both poles of a predisposition have their strengths and blindspots and furthermore, if a predisposition does play itself out in a behaviour, a behavioural strength in one situation may be a behavioural blindspot in another.

Whilst some measures used pejorative terminology in the reported profile, others used socially desirable terminology in the questionnaire. According to Dunette (1972), one in seven people ‘fake good’ in personality tests. In other words, they try to create a profile which they think will be more favourable than their real profile for the specific context their profile will be considered in. One in seven is a relatively high proportion of test takers, but is a reality. Whilst such faking behaviour relies on the test taker making an accurate analysis of the ‘right’ profile and then being able to pick the questions correctly which assess the predispositions they want to portray (two things which are by no means easy), it was Dr Glowinkowski’s view that certain tests made such faking behaviour easier. To give an example, if individuals are being assessed for a sales role, asking if that person enjoys trying to persuade people is unlikely to get a negative response, whether it is actually the case or not. Whereas, if an individual is being assessed for their own personal, private benefit (as is the case with Q) there is no incentive to fake responses – in fact, there is every reason to be entirely honest.

2. Conceptualisation

It was Dr Glowinkowski’s view that if the measure used was going to be applied to a particular setting, presenting the output in language which is directly relevant to this world was a must – using terminology which is concrete, definable and immediately applicable to the person being assessed is hugely important. Getting this right comes partly from the rationale for the development of a test – was it developed for a business application, or clinical application, or some other reason? If a test was not developed for business for example and then did not ‘cut its teeth’ during the initial development and validation phase, it is unlikely the language will match the need. Furthermore, without an understanding of where and how the measure will be applied, the language may appear to be right but in practice miss the point.

In Dr Glowinkowski’s experience, several of the commercially available psychometric measures fell into the trap of having conceptual issues. Where the labels used to describe the poles of a dimension were not immediately apparent in their meanings, valuable time was spent in feedback explaining what the dimension was about.

3. Statistical specifications

Validity (that is, whether a test measures what it purports to measure) is the key concept. Dr Glowinkowski felt that he encountered too many feedback sessions where the data shocked the person assessed as it was at odds with data they had received in the past. Other individuals simply could not see how a profile related to them. This wasn’t a situation Dr Glowinkowski wanted to be in as a consultant.

Outputs of some tests revealed distributions in the dimensions that Dr Glowinkowski was not comfortable with either. The validity of tests was thrown into question where the population was strongly skewed towards one end of a dimension without a good explanation why. In other cases, this situation was apparent in males but not in females, in one culture but not in another and similar questions of validity were sparked.

4. Practicality

Personality ‘types’, where an individual is either one type or another, are immensely useful in feedback, but in exchange for the simplicity of ‘type’ you lose the richness of dimensions. In dimensions of personality you have a level of detail unavailable in types.

Dr Glowinkowski also found with many of the tests that those assessed were unable to link the profile to their everyday life. They found the data interesting but were left with the feeling of ‘so what?’. Partly because of the way the language was used in the labelling of some of the data points, partly because of the way the output was presented, individuals struggled to see the relevance to their lives.

5. Predisposition and Behaviour

Predispositions are preferred behaviours, things people have a preference for and feel comfortable doing. Actual behaviour on the other hand is delivered, it can be seen, it is concrete and although it is influenced by predisposition, the two are not one and the same. Although this boundary is a clear one, Dr Glowinkowski found too often that many of the existing commercially available tests blurred it, confusing the difference between two separate things and presenting them as the same.

It is perfectly possible to measure predispositions, motivation, competencies, values and any number of other things in one questionnaire, but they cannot then be presented back without distinction as if they are the same. This is a practical problem as it causes confusion in those assessed and a theoretical problem as it confuses distinctly different factors. Not only are predispositions different from behaviour and, therefore, competencies, they also give no reliable indication as to ability and, therefore, competence. In addition to these problems, confusing predisposition with values and motivation confuses the former, which is stable, with values and beliefs being far more transient and susceptible to change. Predispositions hold true for a lifetime, but values and beliefs can change daily.

Dr Glowinkowski felt that whilst the problems mentioned above were not present across every available test (each test had its strengths where certain factors did not fall foul of these problems), there was not a test available which did well in all of these five areas.

The rationale for developing the GPI, therefore, was to meet of all these needs in one measure.

DEVELOPING THE GPI

In developing the GPI there were three key considerations:

- An identification of the key concepts underpinning each of the five dimensions – the sub-dimensions

- An easy self-reporting method that captured each of those concepts

- An easy method by which the data would be presented back.

A key consideration in the development of the GPI was to ensure that the data was presented in a way that makes for ease of comprehension. It was also considered important to get a large amount of information presented in a way that would meet the needs of those who prefer detail as well as those who prefer the big picture. The physical presentation had to aid and abet purposeful and constructive dialogue between the person providing the interpretative feedback and the recipient.

As a result, the data is presented in three overarching models:

- Thinking and Doing Style This presents data relating to the dimensions of Cognition (problem solving – that is, thinking), and Attainment (implementation – that is, doing). Cognition explores ideas, insightfulness, decision making, in other words the way we approach thinking. Attainment explores conscientiousness, delivery and thoroughness – that is, attention to detail in delivery. As a result there was considered a natural logic in combining these factors in terms of presentation style.

- Relating to Others Style This draws together data from the factors of Extraversion and Agreeableness. The logic of this linking again sits in the detail of the model, namely that Extraversion explores drawing energy from being outgoing and engaging with others, whilst Agreeableness explores our propensity to collaborate or be more single minded when interacting with other people. Thus, there is a sense in modelling our level of excitement derived from interacting with others and our expectations from such interactions.

- Managing Emotions Style This model examines the factor of Emotionality which includes Neuroticism. The logic of examining this dimension separately concerns its more sensitive aspects and the fact that it presents some fundamentally pejorative concepts. This is overcome by the vocabulary used and the subtle manner that this enables some very personal issues to be discussed.

THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE GPI

Nineteen bipolar dimensions were developed (since reduced to eighteen), each assessed by between eight and ten items. Examining each facet from a number of angles helps avoid acquiescence, nay-saying and lying. Individual items were tested for relevance and reliability. The total number of items in the list after three versions was 182. The item style is completing the sentence. For each item, the beginning is “I am the sort of person who …”, and each item is then followed with “thinks …”, “likes …”, “feels …”, “is …”, etc. The answer style is a sliding five-point scale of agreement, from “Strongly Disagree” (1), “Disagree” (2), “Neither agree nor disagree” (3), “Agree” (4) to “Strongly Agree” (5).

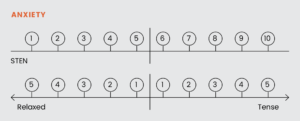

The raw data from the items is added to get the raw facet scores, and these are matched against normalised data and converted to the standard ten (sten) scale. In feedback, the sten is changed somewhat so that each score is from one to five on the relevant pole of the dimension. For example, an individual may score a sten of 10 for Anxiety. However, since Anxiety was made bipolar, ranging from relaxed to tense, the feedback for the test shows a score of ‘Tense 5’. Similarly, a score of Anxiety at sten 1 gives a score of ‘Relaxed 5’ as shown in the figure below. This method also ensures positive feedback; a high or a low sten score now translates to the high end of the dimension. Any subject with a mid-range score will not put negative inference on the lower number quoted in their feedback because it means they are in the middle.

The split-sten scale also proves useful in situations of graphical representation of behaviour, allowing two dimensions to be compared as axes to produce four quadrants, where the individuals score of +/- 1 to 5 for each dimension are converted to x and y coordinates and plotted.

VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY STUDIES

The broad outcomes of validity and reliability studies into the GPI are summarised in The Science Q website page.